JavaScript Engine

A JavaScript engine is simply put - a program that executes JavaScript code. Each browser has its own JS engine. Firefox has SpiderMonkey, Microsoft Edge has Chakra, Opera has Caraken, etc. These are all customised JavaScript and WebAssembly implementations depending on the browser’s architecture. The most widely used is of course, Google Chrome browser and its engine is called V8.

V8 is built mainly with C++, and it powers Chrome as well as NodeJS which is a JS runtime to build server-side applications.

What does the JS Engine consist of?

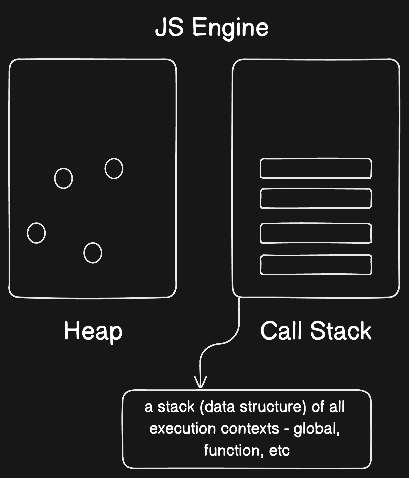

The JS Engine has two main components - a Call Stack and a Heap.

The Call Stack is where our gets executed using something called the Execution Context. The Heap is an unstructured memory pool which stores all the objects that our application needs. We will discuss this in detail soon below, but let’s rewind for a bit here.

Remember in our previous post we had read that JavaScript is an interpreted language? Well, it is not 100% true since interpreted languages are much slower than compiled languages and modern applications cannot afford to be that slow. This is why the modern JS Engine now has a mix of compilation and interpretation - called Just-In-Time compilation.

Compilation - The entire source code is converted to machine code once, and a binary file is created which contains this converted machine code; finally this file will be executed later by a computer. Compilation is done “ahead of time”.

Interpretation - The source code is “interpreted” and executed line by line by the interpreter. In other words, compilation and execution are done sequentially, line by line. The downside is that multiple executions of the same source code will be interpreted again and again.

Now that this above difference is clear, JIT is a bit easier to understand. The ahead-of-time compilation still exists, but no file exists to be executed. The execution happens immediately after compilation - which is perfect for JavaScript to do compilation and execution simultaneously rather than line-by-line interpretation.

How does the code get executed?

As discussed before, our code first enters the JS engine to begin the process of execution.

Once the code enters the engine, it is parsed - which means the code is being read. This code is parsed into a data structure called the “AST” - Abstract Syntax Tree.

This AST is then compiled into machine code - and finally is executed immediately in the Call Stack.

Now this is the most important piece of the puzzle - what is the Call Stack and where did it come from? To understand this, let’s start off with a diagram -

MDN defines call stack like this - A call stack is a mechanism for an interpreter (like the JavaScript interpreter in a web browser) to keep track of its place in a script that calls multiple functions — what function is currently being run and what functions are called from within that function, etc.

Essentially, it is used to keep a record of all the execution contexts (more on this below) - global execution context, function execution context, etc - in an order which are then executed by the JS engine.

Consider the following code -

function calculate() {

// random code

// ..

add()

// some other code after add() function

// ..

}

function add(a, b) {

return a + b

}

calculate()

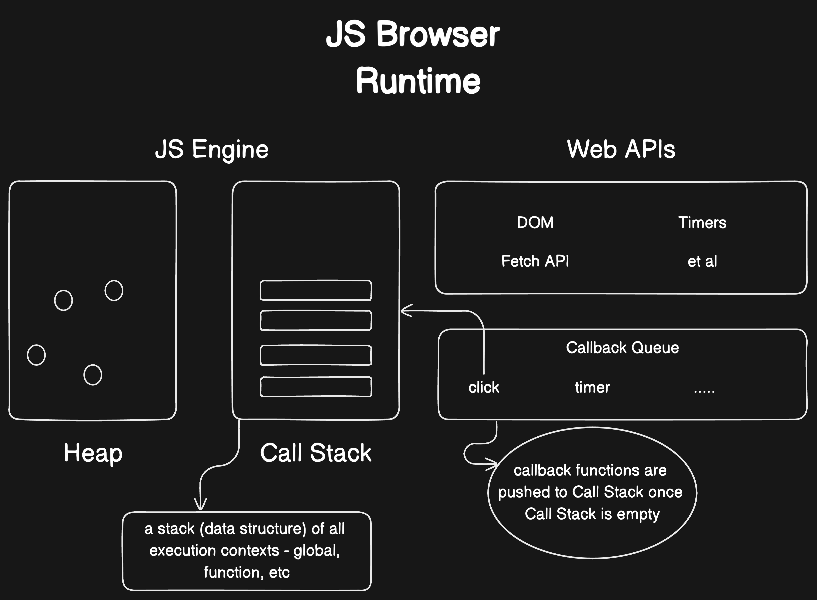

Here, all the functions, both global and inner, are collected and put into the call stack in a certain order to be executed later on. If there are any Web APIs like fetch, timer, etc then they will be pushed into the call stack for execution only once the call stack is empty - meaning once all the functions within call stack are processed, only then will these API methods be pushed into the call stack. This is because these web APIs are not part of the native JS engine itself; rather, JS gets access to these APIs through the global window object. This process can be visualised like so -

All the callback functions that add and enhance interactivity to our web apps - onClick, setInterval, etc are first put into a data structure called the Callback Queue. And then, as mentioned before, once the Call Stack is empty, the callback functions are pushed to the Call Stack for execution.

How exactly do these callback functions get pushed to the Call Stack, and when does the Callback Queue know when to push?

That’s exactly where the Execution Context as a concept wins 😎 Let’s see how it works, below.

Execution Context

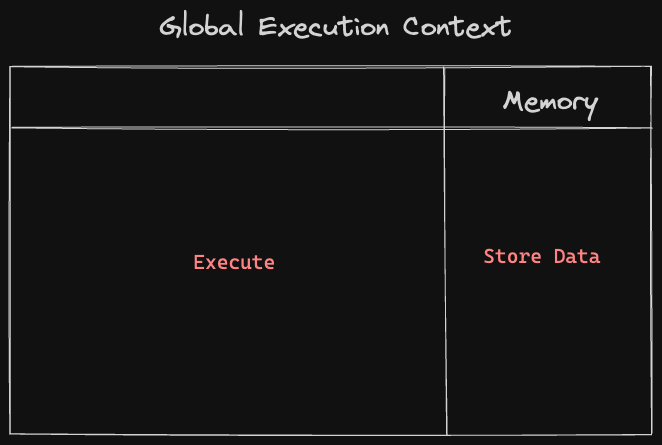

Simply put, Execution Context is an environment created by the JS Engine when code begins executing. This environment is for top level code - variable and function declarations only. Take a look at the diagram below -

As you can see, the Execution Context here is named “Global Execution Context” (GEC) - which is what gets created by the JS Engine when the program is run for the first time.

GEC has two sections - one for storing data (variables, functions, etc), and another for execution of the program (returning values). Now that we know what an Execution Context is, let’s understand how code is actually executed by the GEC.

Following the creation of a Global Execution Context at the beginning of the program execution, the thread of execution of the code happens in two phases -

- Declaration Phase

- Execution Phase

Consider the following code -

let numOne = 21

function square(num) {

return num * num

}

let result = square(numOne)

let username = 'Arya'

function greet() {

return `Hello ${username}`

}

greet()

Let us examine how this code gets executed phase by phase in the Execution Context. As soon as we run the program, the JS Engine creates a Global EC as we saw earlier.

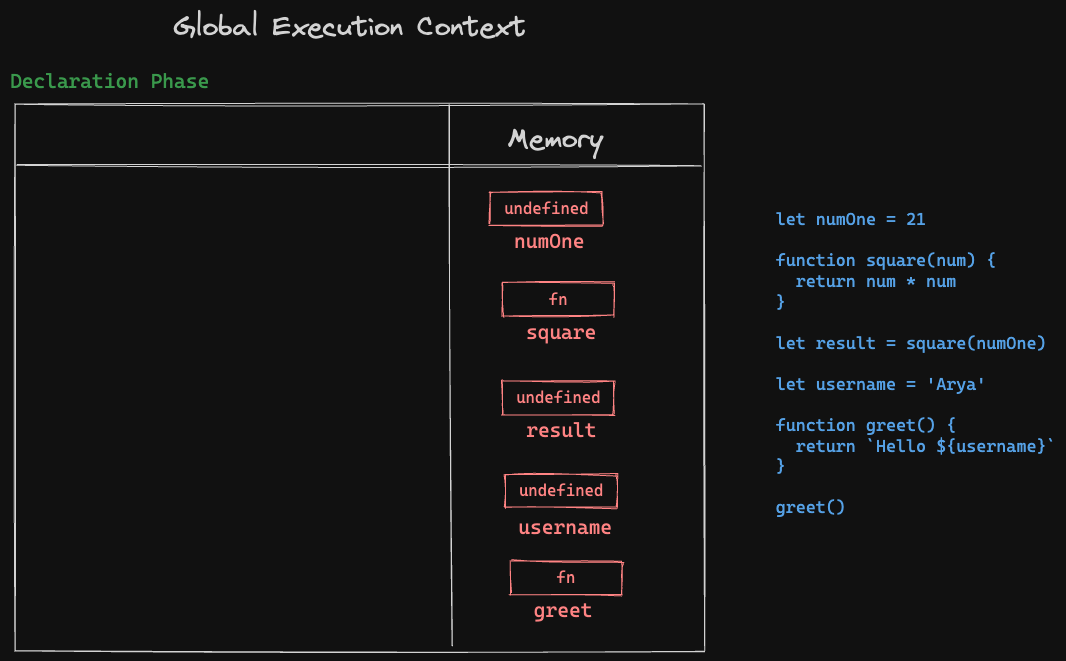

Declaration Phase

Once the GEC is created, we enter the Declaration Phase -

- Now, the first line of code -

let numOne = 21is a variable declaration. Note that declaration and assignment are two different things.let numOneis a variable declaration, whilenumeOne = 21is a variable assignment. So, in the GEC, within the Memory, a variable with the namenumOneis created with its value being currentlyundefined- since we are still in the declaration phase. - The next line,

function square(num) ...is also a function declaration which has an argumentnum- so, for all purposes, this function is a declaration of variable again. Again, in the memory, a function variable with the namesquaregets created with. Whatever is within the function block is ignored for now. - Next, we have

let result = square(numOne)which is a variable declaration since we are assigning the function call ofsquare(numOne)to a variable calledresult. So,resultgets stored in the Memory - again with the valueundefinedfor now. - Next up, we have the variable

let username = 'Arya'- same as the above step. - Lastly, we have the function declaration

greet()- which gets created in the Memory.

This entire process of Declaration Phase can be visualised through the illustration below -

Execution Phaase

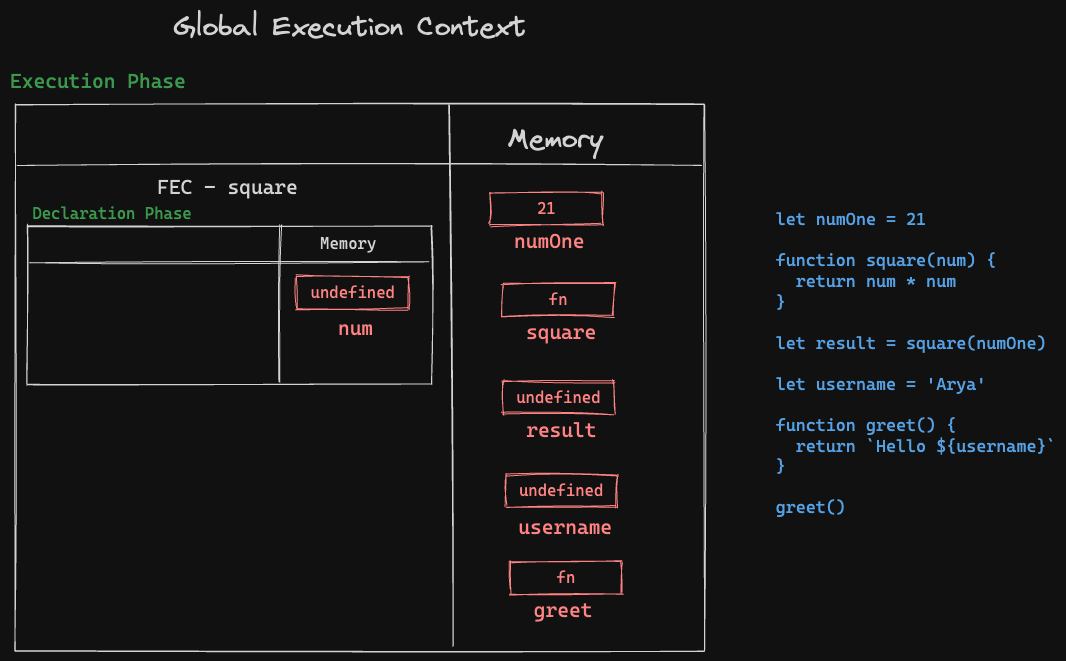

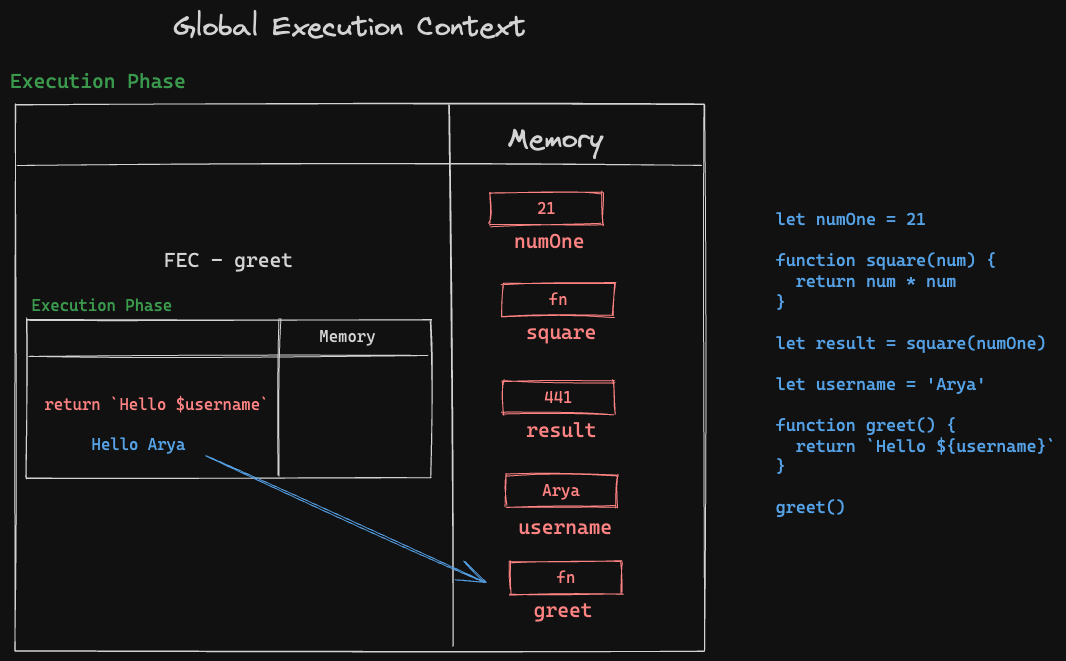

Once the Declaration Phase is done, we enter into the Execution Phase. The execution context looks for all function executions like function calls, return statements, etc here. This is the thread of execution that follows for the above code -

numOneis assigned a value of 21, so in the Memory, the value ofnumOnechanges fromundefinedto21function square(numis just a declaration so this block is skipped.- Next up, we have the

resultvariable being assigned a function callsquare(numOne)- this is where an important part of the Execution Context comes into picture.

Every time the thread of execution encounters a function call, the Global Execution Context creates a separate environment - Function Execution Context (FEC). This means that an FEC is created for each function call in the code execution. And once the function execution is done - which is indicated by return statements - that particular FEC is deleted from the GEC.

So now, continuing the above thread of execution for the variable result -

- A separate FEC is created, with its own Memory and Execution sections. Again, this FEC block follows its own Declaration Phase and Execution Phase.

resultis assigned a function execution ofsquare(numOne).- Now,

squarewas declared earlier with the argumentnum- this argumentnumis also considered a variable declaration for the functionsquare. - A declaration phase begins in the FEC created within the GEC for this particular function.

numis stored in Memory with initial value undefined.

- No other declarations are available in

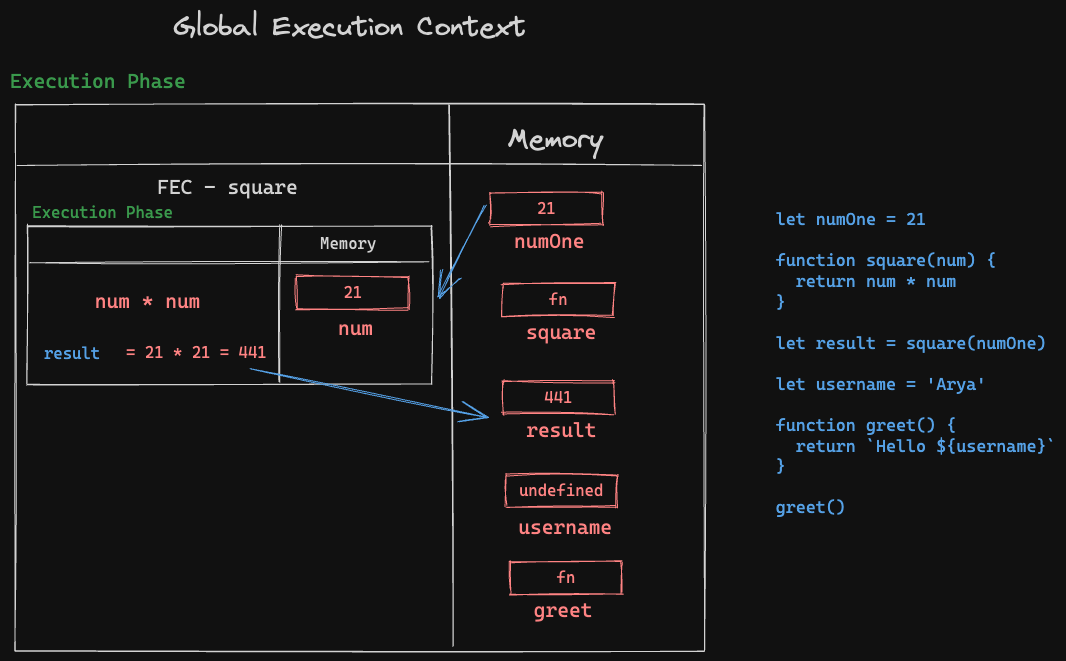

square(numOne), so we enter into Execution Phase. - Now in Execution Phase, we have the value for

numas 21 from the GEC’s Memory; so the value fornumchanges fromundefinedto 21 here. - The function

squarereturnsnum * numso this is executed in the Execute section of the FEC. Since we have the value fornumnow, the value of21 * 21 = 441is calculated and returned. - This returned value of

441is now assigned to the variableresultfor which this separate FEC was started in the first place. - Once this function is done executing, the FEC instance for

squareis deleted.

- Moving on from

resultnow - we have the variableusernamewhich gets the valueAryaassigned to it. - Next, the function

greetis already declared, so we skip this step. - Finally, the

greetfunction is called, which means another FEC is created within the GEC for this function.- Within the FEC, we first go into declaration phase - but since there is no declarations in the function

greet, we move on to the execution phase. - The return statement here calls in the value of the variable

username- which just got a value assigned to it above. - So the statement

Hello Aryais returned, which means the execution phase is done, which means the FEC forgreetfunction is done, which means that the statementHello Aryais returned to the GEC’s Memory, and this particular FEC instance is now deleted.

- Within the FEC, we first go into declaration phase - but since there is no declarations in the function

THAT. WAS. EXHAUSTIVE.

But in a good way though 🤓

These concepts can take some time, and repetition, to grasp a solid understanding of, but these are important to lay a solid foundation of how we write native JavaScript in various scenarios, and also helpful in debugging.

In the next post, let’s study about Scope and the Scope Chain - and why it is important to understand how it works.

Keep shipping 🚀