Introduction

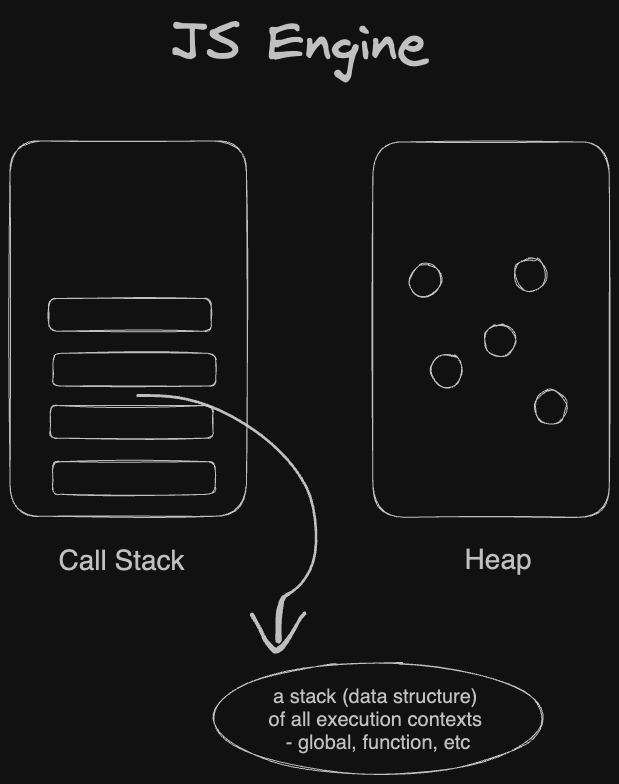

Earlier, when we talked about the JS Engine, we saw there were two important parts that make up the processing engine -

Both the Call Stack and Heap are data structures that are used to store different types of variables. We have already seen the working of the Call Stack in our previous post.

In this post, let’s discuss the Heap memory and what role it plays in memory allocation for different data types in JavaScript.

Primitives vs Reference Types

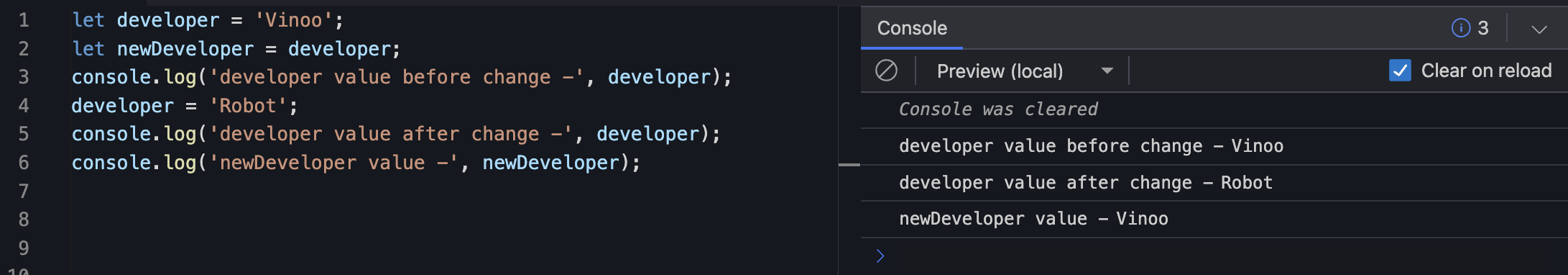

Consider the example below -

Example 1 -

Here, we see that the developer variable had the value of ‘Vinoo’ and then we changed it to be ‘Robot’, and that is what is reflected in the console. The newDeveloper value, which was assigned the value of developer retains the original value even after we changed the original one.

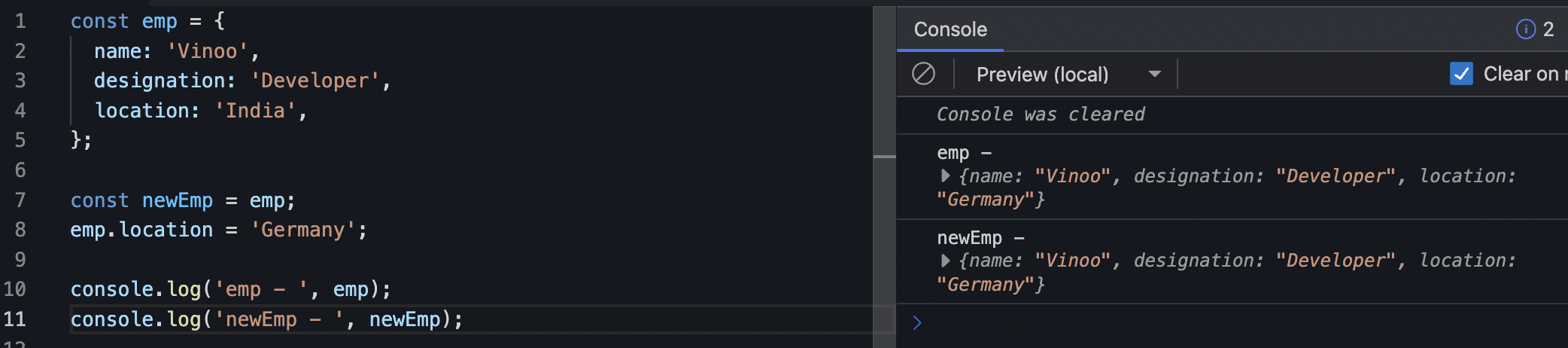

Now consider the below example -

Example 2 -

What we did here was to create an object emp with a few details, and then created another variable newEmp where we essentially copied (assigned) the values of emp to newEmp. And when we changed the value of the age property in newEmp, its value in the original object also got changed.

Why? And how?

Memory Allocation in JavaScript

Primitive types - number, string, boolean, undefined, null, and Reference types - Object literals, Arrays, Functions, etc are called so respectively because of the difference in the way memory is allocated for these types.

Primitive Types -

Primitive types are, well, primitive in nature in the sense that memory is allocated directly to the variables. The Call Stack data structure is where these Primitive values are stored.

In Example 1 above, the variables developer and newDeveloper both get assigned specific addresses in memory, which is why when we change the value of one variable, it does not affect the value of another. Take a look at the illustration below -

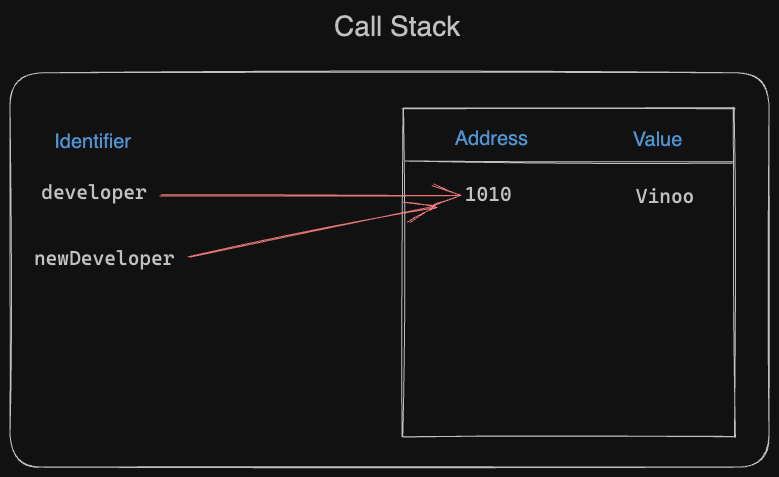

When we create the variable developer, it gets allocated a specific address (say 1010) in the memory - the Call Stack - and then the value ‘Vinoo’ will be stored at this address. developer will actually now point to the address and not the value. Next, when we declare newDeveloper to be equal to developer, what happens is that newDeveloper will not be allocated a new address; instead, it will point to the same memory address as developer. And since the address holds the value Vinoo, the same will reflect when we print the value of newDeveloper to the console.

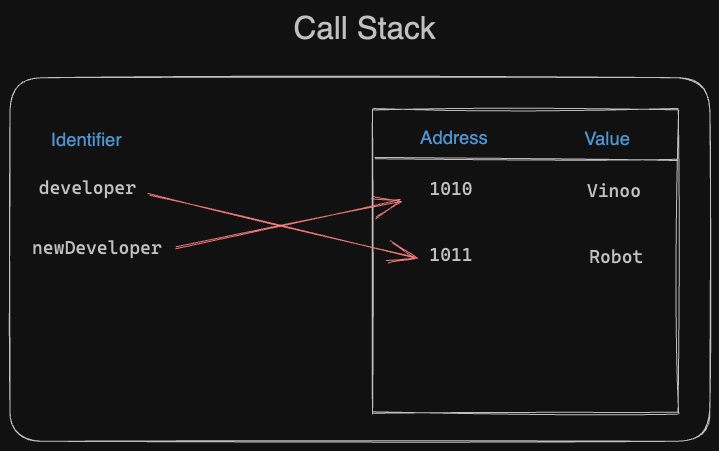

What happened when we change the value of developer to ‘Robot’? The value at the address 1010 certainly does not get changed. Values stored in the Call Stack memory addresses are immutable in nature - so the address and the value remain unchanged. However, when we change the value of the developer, a new address is created with the new value, and the identifier developer will now point to the new address, while the newDeveloper identifier will still point to the earlier address and value. Like so -

Reference Types -

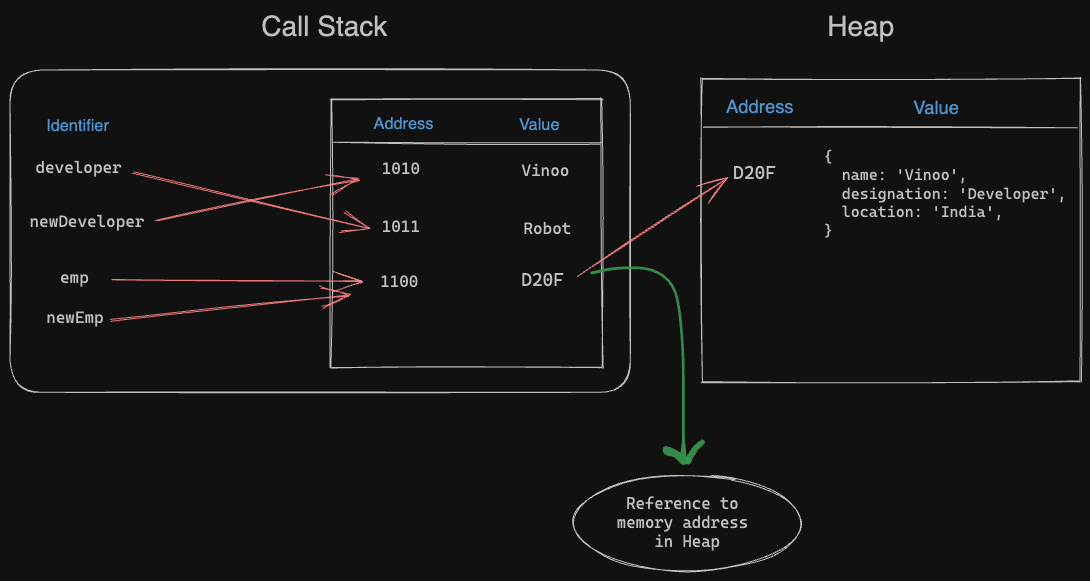

In Example 2 above, we saw how changing the value of one property in the new copied object changed the value for the original object’s property as well. This is because Reference Types are stored in the Heap memory data structure and not the Call Stack directly. The below illustration throws some light -

As we can see, the properties of the emp object are first allocated an address in the Heap memory. The emp identifier is stored in the Call Stack under an address whose value references the address of the properties stored in Heap memory. So essentially, the value of the address of emp in Call Stack is simply a reference to the Heap memory’s address which in turn contains the actual values.

Now, when we declare a new variable newEmp to be equal to emp, the new object just points to the address of the original object, and thereby its values. So when we change the value in the new object, it changes the original values too.

This behaviour is because the new variable newEmp is not really a new object itself; instead, it just points to the value of the address held by the original object, so technically, mutating one of them will mutate the other one too.

How to actually copy objects?

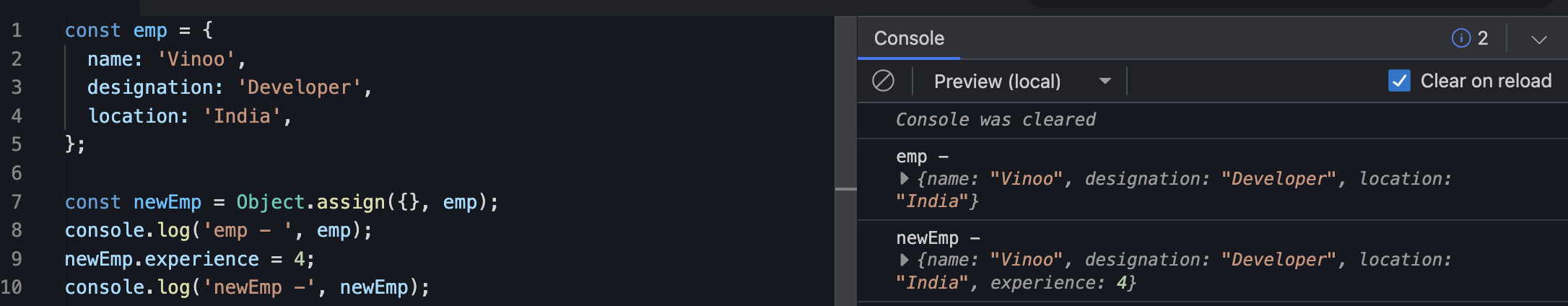

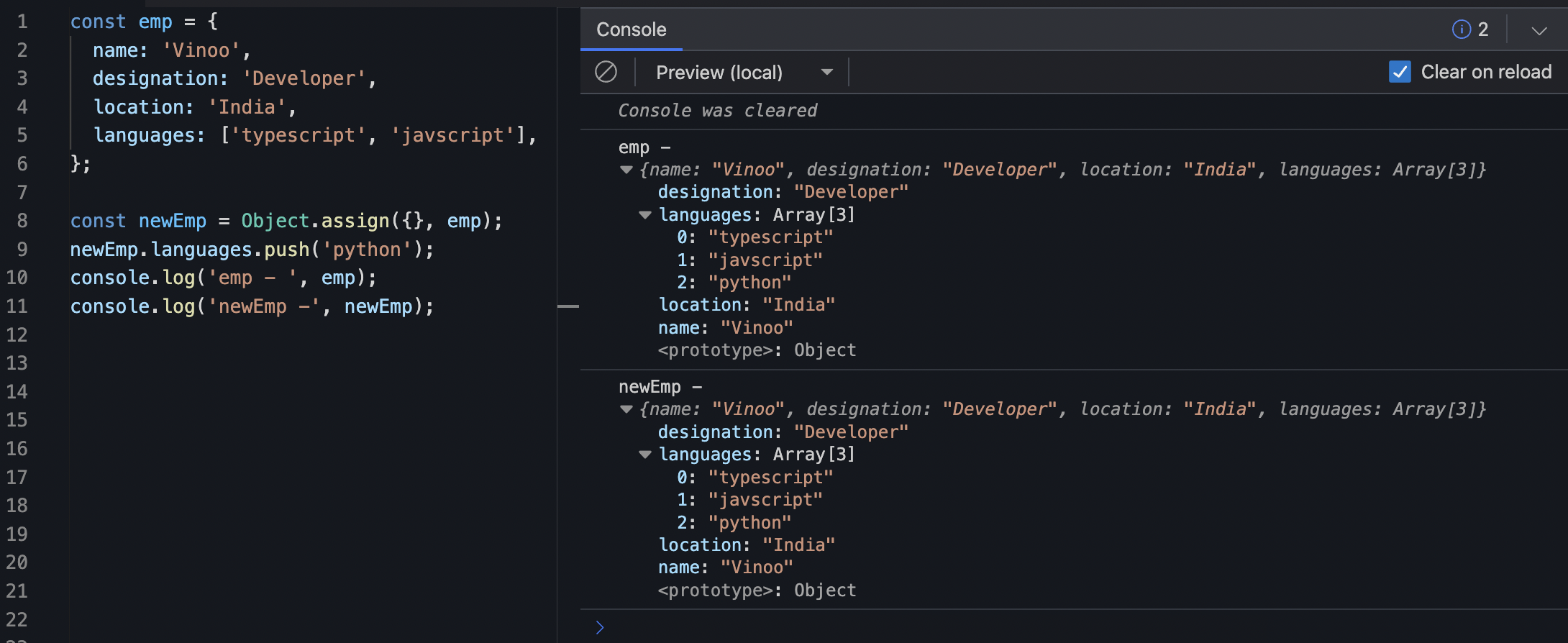

There are multiple ways to do that, and it deserves a comprehensive post of its own, but for the scope of this post, we will look at one of the most basic and common methods - the Object.assign() method. Let’s see an example -

As we can see here, we used the Object.assign() method to assign the newEmp variable to be an object populated with the values of emp object.

Once that was done, we mutated the new object with an additional property yoe - and the original object remained unchanged.

This works well for a single level cloning - or shallow clone - of objects; meaning, that the Obejct.assign() method does not work completely on multiple/deeply nested objects. For example -

As can be seen, even though we only pushed the new item python to the languages array in the newEmp object, the original emp array also got mutated. This is because the array elements are considered to be deeply nested values and Object.assign() method will not be able to do the so called “deep cloning”.

Closing Notes

We will cover more on shallow clones and deep clones in detail in a later post. But for now, this post has covered enough to understand how memory allocation works in JavaScript.

Confusing? Well, hang in there 🥲

See you in the next one!

Keep shipping 🚀